There are moments when the body feels like both a stranger and a home we can never quite return to. Trauma can leave us there—adrift, disconnected, caught in currents we don’t understand. One of the central insights of somatic psychotherapy is that the body itself is the landscape where healing begins. The breath, the gut, the throb of the heart. These are not just background rhythms. They are the frontlines of our aliveness.

The Body–Mind Connection

As Manuela Mischke-Reeds explains in her book:

The Greek word soma means body. Psyche means mind. Together, somatic psychotherapy is the study of the body–mind interface.

To reference the soma in therapy is to reference the ability to sense oneself through raw, lived sensations.

This sensing, also known as interoception, is our capacity to feel the body in real time: the rise of emotion in the chest, the soft ache in the stomach, the restlessness in the legs.

The Vagus Nerve: Our Body’s Superhighway

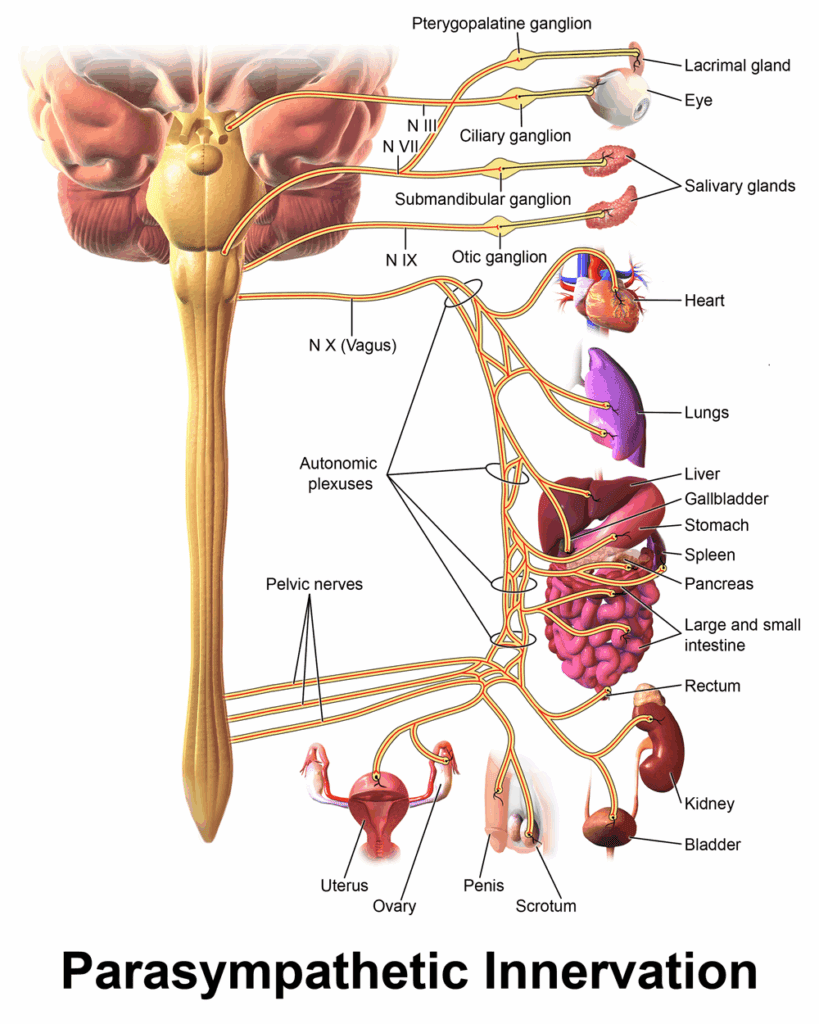

The Vagus Nerve is the longest, most complex cranial nerve, which is why it’s derived from the Latin word vagus, meaning “vagrant, wanderer”. It innervates the muscles of the throat (pharynx and larynx) and the organs of respiration (lungs), circulation (heart), digestion (stomach, liver, pancreas, duodenum, small intestine, & the ascending and transverse sections of the large intestine), and elimination (kidneys).

In simple language, the vagus nerve connects brain and body. Originating in the brainstem, it branches through the neck and torso, reaching lungs, heart, and gut. Remarkably, about 80% of vagus fibers are afferent, sending information from the body up to the brain. This means our gut, our heart, and our organs constantly shape what the brain perceives as reality.

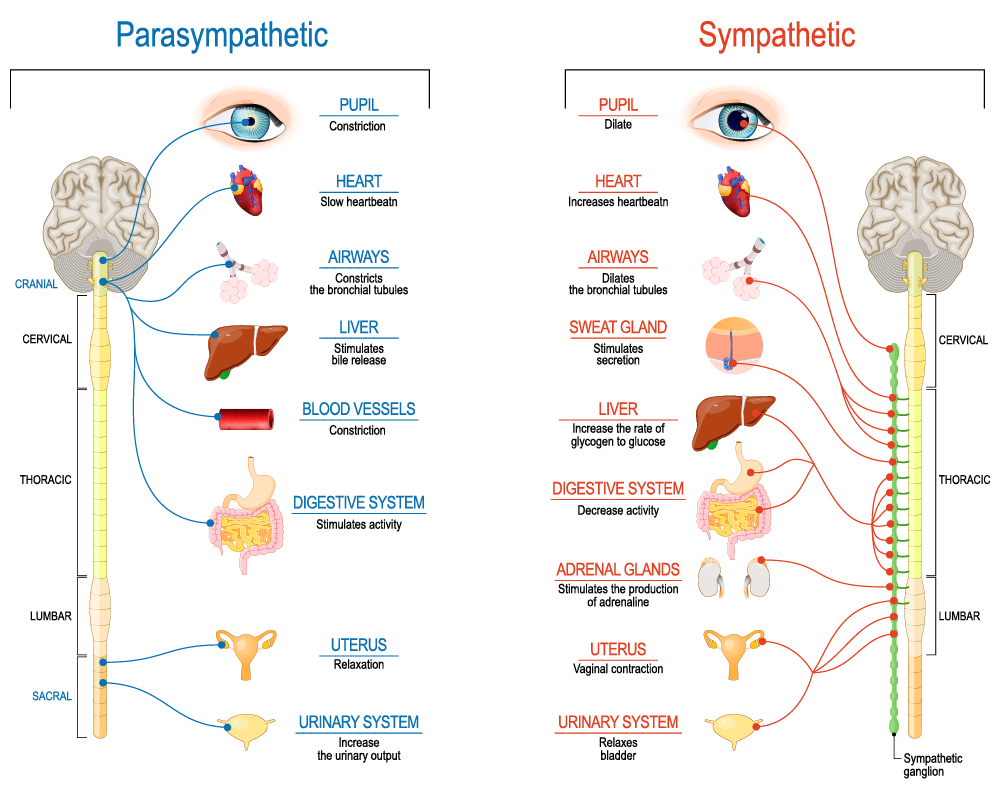

When trauma is unresolved, the body can remain locked in defense—fight, flight, freeze, fold, or collapse. This neuroception, the nervous system’s unconscious scanning for threat, keeps signaling danger long after it has passed. The result: chronic tension, gastrointestinal distress, panic attacks, and even the embodied experience of heartbreak.

Interrupting the Feedback Loop

How do we interrupt this cycle?

Not by talking the mind into safety, but by sending new signals through the body. By teaching the nervous system, through vibration and breath, that the storm has passed. This is the promise of somatic psychotherapy.

Voo Breathing

Developed by Peter Levine, Voo Breathing is a simple yet powerful practice:

- Inhale deeply.

- On the exhale, vibrate the sound “voooooo” from deep in your belly.

The vibration stimulates the vagus nerve, sending a message upward: safety is here.

Within minutes, Voo Breathing can shift us—awakening a shut-down body into liveliness, or softening a hyperaroused state into calm. It is a return to balance, a reminder that healing is possible.

Try it yourself: A Simple Exercise to Ease Despair with Peter Levine, PhD.

Embodied Self-Awareness

Allen Fogel describes embodied self-awareness as “our ability to pay attention to ourselves, to feel our sensations, emotions, feelings, and movements online, in the present moment, without the mediating influence of judgmental thoughts.”

Feelings and emotions are often understood as interchangeable. They are interconnected, but distinct:

- Emotions are primal, sensory-based responses: biochemical shifts in the brain, instantaneous and physical.

- Feelings arise later, from the cortex. They give meaning to what began in the body.

As neuroscientist Antonio Damasio writes, feelings are “mental experiences of body states as the brain interprets emotions.”

In other words, emotions spark the fire; feelings are the story we tell about its heat.

Most of us live estranged from this awareness. We only tune in to our bodies when pain demands it. Somatic psychotherapy invites us to notice sooner, to return daily to the subtle, constant conversation between body and mind.

A Practice: Coming Back to the Body

Pause for a moment. Bring your attention inward:

- What sensations do you notice? Tingling, warmth, heaviness, fluttering?

- Where in your body do these sensations begin and end?

- What are your shoulders, jaw, or spine doing in this moment?

There are no wrong answers. Only the tender practice of noticing and noting what happens next.

Here are some words to help you name what you find:

neutral, alive, soft, tense, clenched, heavy, open, cold, knotted, relaxed, spacious, throbbing, numb.

The point is not to fix. The point is to listen.

Closing

The body is not just a container for the mind; it is the mind’s fiercest ally and oldest archive. Trauma writes itself into muscle, gut, and breath. But through practices like Voo Breathing and the wider lens of somatic psychotherapy, we can begin to rewrite.

Slowly, steadily, one vibration, one subtle movement at a time.

PS: Here’s an additional resource to stimulate the vagus nerve for self-regulation: 3 simple guided exercises for anxiety

If you’re curious about exploring these practices more deeply, I offer somatic psychotherapy for individuals and couples. Visit my services page here to learn more.

Sources: