A South Asian therapist’s reflections on family roles, identity, and what it means to set boundaries for ourselves.

Growing up in South Asia, specifically, Nepal, I was assigned a family role long before I had the language to name it, let alone understand what it meant to carry it. Like many raised in collectivist cultures across Asia and South Asia, I was shaped by values of family unity, mutuality, cooperation, and social harmony. It meant being part of close-knit communities where people looked out for one another. Where families lived together, joint-family style, and neighbors often knew as much about your life as you did yourself.

In that world, you didn’t just represent yourself. You carried your family’s name, your reputation stitched tightly to theirs. You learned early how your actions reflected the family’s standing in the unspoken, yet deeply felt honor code system.

In such systems, peacekeeping and obedience are prized. The message, often unspoken but always clear, is this: Don’t talk back. Don’t make eye contact. Do what’s asked of you because that’s how you show love, respect, and care. Especially for South Asian women, these rules shaped how we learned to move through the world, and where we understood ourselves to belong.

It’s no surprise, then, that many South Asian adults struggle with values like autonomy, agency, and boundaries. We were wired for connection and compliance, not self-expression or space. We were rewarded for being agreeable, adaptable, quiet. Not for speaking our needs out loud.

And yet, there’s something undeniably human in the longing for authenticity—for the desire to be known, not just for who we’ve been asked to be, but for who we actually are. That longing shows up again and again in the therapy room, especially in the work I do with other South Asian therapists and clients. A shared wondering: “How do I matter? To whom? How do I find myself when I’ve spent so long living as an extension of others?”

Of course, these questions aren’t exclusive to South Asian communities. I’ve heard them from many clients here in the U.S., especially those raised in families where roles and rules mattered more than emotional expression. Individualism may be glorified in the West, but even here, many still struggle to balance their own needs against the expectations of family.

Because as humans, we try to find ourselves within our relationships—our families, our friendships, our partnerships, our communities. Where we stand in those systems can feel like a matter of emotional survival. And often, it is. We survive through belonging. We survive by adapting to the people and systems that hold power over our access to care, connection, and resources.

The Roles We Carry

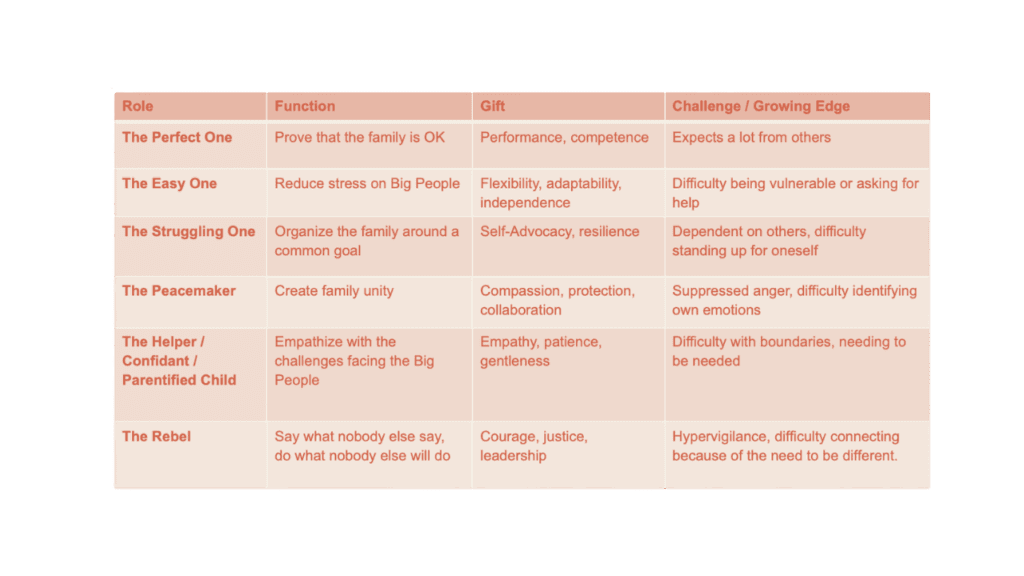

Let’s come back to family roles, the ones many of us were given early on, whether explicitly or through the emotional undercurrents of our homes. I came across this helpful list through a training led by Dr. Alexandra Solomon, an author/therapist. You might recognize yourself in one or more of them:

Other common roles that aren’t listed in the chart:

- The Responsible One

- The Strong One

- The Caretaker

- The Scapegoat

As you sit with the list, consider these:

- Which role do you most identify with, and why?

- In what ways do you still carry this role into your adult relationships?

- How has it served you and how does it hurt you?

- In Dr. Solomon’s words, “when have you put that role into retirement?” (For example: not rescuing someone when you were always The Helper. Or expressing a need when you were always The Easy One.)

- And if you’re in a relationship, ask yourself:

- What do I want my partner to understand about this role I play?

- Is there something they could do to support me as I work to step outside of it?

Boundaries: A Complicated Practice

Let’s talk about boundaries as you reflect on your family role.

Boundaries can be defined as our ability to set limits with others and to recognize and respect the limits others set with us. They also help us sense where we end and others begin, to distinguish between what’s ours and what belongs to the outside world, including thoughts, emotions, and expectations.

As a South Asian adult and as someone who’s long inhabited both The Helper and The Peacemaker roles, boundaries have always been hard to recognize, let alone express. I learned about them late in life. It wasn’t until graduate school, at age 28, that I even encountered the concept.

My relationship with boundaries is still evolving. As with many of my clients and other South Asian therapists or children of immigrants, my history with them is tangled. And I too wonder:

What are boundaries really? What do they offer me? What do my boundaries look like, uniquely shaped by my relationships, my culture, and my nervous system?

And I suppose the hardest part isn’t understanding them. It’s honoring them. Implementing them. Holding them. Especially, when they’re crossed not out of malice, but out of habit or unfamiliarity. Or when I haven’t clearly expressed them. Or when asserting them stirs guilt in me, or defensiveness in others. Sometimes, when we begin to shift, it can feel like a threat to the balance others rely on. Not everyone is ready to change just because we are.

Boundaries ask us to pause, reflect on the roles we’ve carried, and gently ask:

- Who do I want to be now?

- What values do I want to embody today?

Boundaries, Values, and Backdrafts

For me, I want to be an honest partner, an honest daughter, sister, and an honest friend. Without honesty, I betray myself, and others, by hiding my true feelings and truths. That disconnection impacts my sense of closeness. So if honesty is a value I hold dear, then I practice boundaries not to push others away, but to live in greater alignment with myself.

What about for you? What values do you want to live by?

One of the biggest emotional hurdles to setting boundaries is “backdraft”—a term from self-compassion work. It describes the painful feelings that often rush forward when we begin treating ourselves with care for the first time.

Backdraft is a firefighting term: when you open the door to a burning house, flames explode outward. In self-compassion, when we begin to offer ourselves kindness, long-buried pain may surface. Guilt, shame, fear. But this isn’t failure, it’s a sign that healing is unfolding.

As author/therapist Prentis Hemphill writes:

Boundaries are the distance at which I can love you and me simultaneously.

Setting boundaries is one form of “fierce self-compassion”—standing up for ourselves with love, courage, and clarity while holding onto our connections. Yes, guilt may arise. Yes, shame may whisper. But these emotions are signals. Not truths. What then guides us instead are our values.

We can still sit with our feelings. We can witness them. But we don’t have to “obey” them.

If you’re a South Asian adult beginning to unpack old family roles, navigating the tender work of boundaries, or longing to reclaim your voice, you’re not alone. These themes show up often in my work as a South Asian therapist. If you’re seeking support from South Asian therapists or gently exploring what boundaries might mean for you, I invite you to visit my website and reach out.

If you’re a trauma survivor, then boundaries come with a different weight and meaning. Please review my post on trauma and boundaries.

Let’s keep finding our way home… back to ourselves.